THE NET OF FAITH

by Peter Chelčický

translated by Rev. Enrico Molnár

When God commands a thing to be done against the customs or compact of any people, though it was never by them done heretofore, it is to be done.

– St. Augustine

This yearning for a life of more abundant Christian expression was incorporated in Chelčický’s greatest work, the Net of True Faith, written sometime between the years 1440-1443, during the interregnum following the death of King Albrecht of Hapsburg.[106] His whole philosophy of life and history is represented in this book. Its central theme is the relation of the Church and state, and the Christian’s place in that relation. The thesis is presented in the form of an exposition of the story of the miraculous “inclusion of fishes” according to Luke’s narrative (5:4-11). As far as we know, this is a unique interpretation of the gospel story; in most medieval treatises, learned men and theologians wasted themselves in fanciful trivialities. But Chelčický, starting with his allegory and bringing out its ethical, political, and economic implications goes far beyond these stereotyped commentaries. In reading his interpretation of the story we realize that

rarely have any advocates … whether ancient or modern, worked out its implications with such rigorous logic, such thoroughgoing consistency, and such singleness of aim, as Peter Chelčický had done.[107]

In his allegory, the net becomes the symbol of the Christian religion; in the net there is a multitude of fish caught by the apostles who are aided by Jesus. They represent the Christians. The loving will of God offers to men His net of faith in Jesus Christ and with it his salvation. And so there comes down into the sea of human bondage, sin, and misery a veritable symbol of the divine agapé, the net of faith, to do its work of redemption. But the net became greatly torn

when two great whales had entered it, that is, the Supreme Priest wielding royal power and honor superior to the Emperor, and the second whale being the Emperor who, with his rule and offices, smuggled pagan power and violence beneath the skin of faith. And when these two monstrous whales began to turn about in the net, they rent it to such an extent that very little of it has remained intact. From these two whales, so destructive of Peter’s net, there were spawned many scheming schools by which that net is also so greatly torn that nothing but tatters and false names remain…[108]

A Miniature Drawing from the Book Hortus Deliciarum

The nearest resemblance to Chelčický’s net of faith in treatment and motif that we could find is contained in the noted Hortus deliciarum of the Abbess Herrade of Landsberg[109] which reproduced pictorially an idea founded on the Book of Job (41:1ff),[110] and of which Mâle traces the seminal thought back to St. Jerome in the 5th century, and thence down through St. Gregory the Great,[111] St. Odo of Cluny,[112] and Bruno of Asti,[113] to Honorius d’Autun who thus described the symbolism:

Leviathan the monster swims in the sea of the world, i.e. Satan. God has thrown the line into that sea. The cord of that line is the human genealogy of Christ; the hook is the divinity of Christ; the bait is his humanity. Attracted by the scent of his flesh, Leviathan wants to snap him, but the hook tears apart his jaw.[114]

The background for Chelčický’s allegory is his belief in the so-called Donation of Constantine, a belief, by the way, based on the authority of John Hus,[115] and probably also on the Waldensian version of the Donation.[116]

There was drawn up, presumably in the papal chancellery during the third quarter of the eighth century, a forged document alleged to be a donation of the Emperor Constantine[117] to Pope Sylvester I.[118] This document relates that when the pagan Constantine was healed of leprosy, by the pope, he professed Christianity. In gratitude he decided to vacate Rome, removing the imperial capital to Constantinople. As his legacy to Sylvester he left

… our imperial Lateran palace, … likewise all provinces, places and districts of the City of Rome … and bequeathing them to the power and sway of him and the pontiffs, his successors, we do … determine and decree that the same be placed at his disposal, and do lawfully grant it as a permanent possession to the exalted Holy Roman Church … The Sacred See of Blessed Peter shall be gloriously exalted above our empire and earthly throne … And the pontiff who for the time being presides over the most holy Roman Church shall be ruler as well over the four principal sees, Antioch, Alexandria, Constantinople, and Jerusalem…[119]

The papal theocracy based its whole legal justification on the imposing Petrine theory combined with the forged Pseudo-Isidorian Decretals,[120] of which the Donatio Constantini is just one document. All men of the Middle Ages believed in this donation, and so did Peter Chelčický.[121] It was often quoted by popes and papal partisans in their subsequent struggles for temporal power.[122] For seven hundred years it was believed to be authentic, even though there were men who wished it were a forgery, which Nicholas of Cusa[123] had suspected, but the honor of discovering their falsehood was left to Lorenzo Valla, the famous Italian humanist,[124] who showed in a scathing work of 1440, De falso credita et emendita Constantini donatione declamatio, that its Latin could not possibly have been written in the fourth century. Be it as it may, the fact remains that by the Edict of Milan[125] Constantine raised Christianity to equality with the public pagan cults; the final act was the seizure of the power of the state and the banning of other competing cults.

By utilizing the mechanism of the State, the Church lived through the ruin of the State and lived to tell the tale. That act betrayed the spirit of Jesus and established the reign of Christ…[126]

Constantine insisted upon unity within the Church and hence was drawn into the problems of sectarian strife. In this sphere he undertook to uphold the opinion of the majority of bishops and exercised the right to summon and preside over councils and to validate and enforce their decisions. This exercise of imperial authority in religious matters was the initial step in the development of caesaro-papism.

Frontispiece Illustration of the 1521 Edition of The Net of Faith

Printed in the Monastery of Vilémov

(The net is held by four apostles and in the net are the righteous Christians. One sinner is falling overboard and another is escaping through a big hole in the torn net. Below, protruding from the open jaw of an infernal leviathan, the devil is roping in the pope, the emperor, the learned doctors, and other sinners.)

Chelčický did not possess the phenomenal historic knowledge of Lorenzo Valla, and he never heard of the latter’s discoveries. He did not doubt the authenticity of the Donation but he attacked its juridical validity on ethical and Biblical grounds. It is a strange coincidence that both books, The Net of Faith and the Declamatio de Donatione should have been published almost simultaneously.[127] Each of these books, one written in humanist Italy, and the other in “heretical” Bohemia, represented a mighty blow at ecclesiastical imperialism and falsehood.

Chelčický’s historic presupposition was wrong but his ultimate analysis of the secularization of the Church and its identification with the temporal power was correct. Mythologically, the Donation presents a profound truth. It was when the Donation took place, according to Chelčický, that the “two great whales” – the Emperor and the Pope – entered the net of faith, “rending it in many places.” Declaring the law of God to be the sole rule of faith and life, he postulated the abolition of all church institutions not compatible with this law and introduced by man, as well as the abrogation of all secular institutions, social orders, and state orders inconsistent with Christ’s law of love.

Chelčický antedates Kropotkin by several centuries when he writes that the state is based on violence, plunder, and proud individualism.[128] But where Kropotkin speaks in terms of economics, Chelčický speaks with prophetic earnestness in terms of a theocentric history. As he sees it, Gideon, the “faithful Jew” of the Old Testament, answered his followers with true divine sanction when he refused the crown they had come to offer to him:

I will not rule over you, nor shall my sons rule over you, since the Lord God rules over you![129]

The state has its origin in man’s pride and rebellion against God.[130] Just as the Jews rejected the law of God by inviting Saul to rule over them, so the Christians later on rejected God by accepting the Donation of Constantine.[131] And having its origin in sin, the state has become a tool of punishment.[132] This is well illustrated in the records of King Solomon’s rule that, in all the glory of his wisdom, brought terrible sufferings upon his people.[133]

The state’s existence may be justifiable as a “necessary evil” only for the pagans among whom it works “as a plaster on an abscess”[134] since, if they had “no prince with a sword in his hands,” there would be no justice, but a war of all people against all, and depravity and violence would be the general rule. However, the heathens know not the teachings of Christ who tells us to love our neighbor and to do good to those who persecute us. And Christians? They must abstain from all violence:

Our faith obliges us to bind wounds, not to make blood run…[135]

Therefore, a Christian state is a contradiction in terms. For it is in the nature of the state to rule by coercion and force.[136] However, the rule of Christ is perfect,

and therefore it never uses compulsion… The virtue that he expects from every Christian … springs from a good and free will; originating in freedom, it has the responsibility of choice, to choose either the best or the worst.[137]

A Christian cannot rule, for God is the only ruler.[138] A secular ruler is bound, by virtue of his sovereignty, to use violence and other non-Christian methods.[139] If he should, perchance, become a Christian, his only means of ruling would then be persuasion, that is, preaching:

… for otherwise, by forcing Christians, he will not succeed. But if a king … preaches, he is not a king any more, he becomes a priest. As a king he should be able to do naught but hang all evil men. For no king, not even the best one, could succeed in rehabilitating an evil people except by the law of Christ.[140]

In this teaching, Chelčický comes very close to the Gelasian doctrine of the two powers.[141] Furthermore, says he, sovereignty goes always hand in hand with aggressiveness and imperialism. It is in the nature of all rulers to use un-Christian means for their ends of aggrandizement:

They try to embrace as much of the earth as they are able, using every means and every ruse of violence to get hold of the territory of the weaker; sometimes by money, and at other times by inheritance, but always desiring to rule and to extend their realm as far as they can.[142]

That is why no Christian can have any part in any government.[143] He is good because it is God’s will and not because the state requires it.[144] His ethic is therefore superior to that of non-Christians who abide only by a legal goodness.[145] For the same reason, no Christian can exercise authority over another Christian.[146] This fundamental postulate underlies all of Chelčický’s philosophy. It carries with it many implications: a Christian cannot tax another Christian[147] – however, if Christians live in a non-Christian state, they ought to pay their taxes for the sake of public peace.[148] A Christian may not perform military service for that means imposition of a coercive burden on other Christians.[149]

Men are governed not so much by the tyrants they fear as by the institutions they love; and what is, therefore, more worth loving than the “sweet rule of Christ?” In the long run love – not fear, coercion, and hatred – will prevail:

O how small and barren is the dominion of pagan kings compared with the dominion of Christ! The temporal power heaps burdens and sufferings upon its subjects instead of freedom and consolation. And yet, the Kingdom of Christ is so powerful and perfect that, if the whole world wanted him for king, it would have peace, and all things would work together for good. And there would be no need of temporal rulers, for all and sundry would stand by grace and truth. The need of kings arises, indeed, because of sins and sinners.[150]

To him who obeys God the state becomes a superfluity, for the fullness of the law is love:

Judge for yourself, how can state authority approach those who are bound by the divine commandment not to resist evil in times of adversity, but to offer the other cheek when the one is struck, to leave revenge to God and not to return evil for evil…?[151]

Chelčický does not argue against any state as such,[152] but against the abuse that such a center of power and violence is given a Christian name and justification.[153] While on earth, the Christians are a true colony of heaven, and the laws of heaven are undefiled by compulsion. These laws are different from the “earthly” laws in that they never enforce obedience; man has to turn away from his evil ways by his own volition; and there are always two alternatives before man:

The Lord Jesus calls us to the best good, the devil and the world call us to the worst evil. Therefore, choose joy or choose hell. The choice of either of these ways is in your hands.[154]

In the fourteenth chapter, one of the most important chapters of the whole book, Chelčický sums up in eloquent words the core of his conviction that “Christ’s commandment of love could make one multitude out of a thousand worlds, one heart, and one soul… It will lead man into the fullest life, it will make him most precious to God, and man will become a gain to man!”[155]

God is the end; love is the means. That is the rule of Christ’s kingdom whose earthly image is the Church. Christ is the true head of the Church[156]; “the beginning of his kingdom is at the end of men’s sins”[157] and his law is love.[158]

This law is sufficient of itself and adequate for a redeeming administration of God’s people.[159]

It is an apotheosis of free will[160] and it functions only when man responds through personal discipline[161] to the divine agapé.[162] The Church comprises all righteous Christians gathered in the Net of Faith by the apostles.[163] As long as Christ was the sole ruler of the apostolic Church – that is, for the first three hundred years, it was perfect.[164] But when Pope Sylvester accepted the Donation of Constantine[165] the net of faith became badly torn.[166] And when he allied the Church with secular power he “mixed poison with Christ’s gospel.”[167] Since then, the social utility of the priestly Church has been to invoke divine sanctions in defense of the status quo, however bad.[168]

Indeed, the Church of Rome rather likes a wicked king, for this man … will fight for her better than a humble Christian.[169]

In order to increase the power of the Church, the Pope arrogated to himself all prerogatives of Christ[170],

and this he manages lucratively, initiating a pilgrimage to Rome from all countries … and proclaiming to all pilgrims forgiveness of all sins…[171]

Through participation in power politics, by condoning wars and even by issuing war bonds for their prosecution,[172] the Church of Rome lost its spiritual heritage. Only those who obey Christ are members of the true Church. The true Church was not to be found even among the Hussites, those “raging locusts.”[173]

Chelčický gave considerable thought and attention to one of the most important and spectacular events of Christendom in his age, the Council of Basel.[174] Out of ninety-five chapters of his Net of Faith he devoted a full fifteen[175] chapters to the Basel proceedings. Needless to say, he was very disappointed in the display of power and ecclesiastical hypocrisy so manifest at Basel. He was scandalized at the Pharisaic ratiocinations proffered by high church dignitaries in the name of Christian truth. The Council may have repeatedly pronounced that the Holy Spirit was presiding over it, but Chelčický saw nothing in it but the work of the devil himself:

Let him who is humble and meek come and behold the vainglorious haughtiness! For a congregation of fornicators has entered into a covenant with the Holy Spirit and the Holy Spirit reigns over them who are an assembly of harlots, assassins of righteous men, and transgressors of all commandments of God… The devil, who dwells among us under a shadow as it were, has a rich accoutrement indeed. And who shall unveil his face, which he hides by the shadow of the Holy Spirit?[176]

He took to task especially the Papal Auditor Juan Palomar,[177] one of the chief opponents of the Hussite position, and the Parisian professor of theology Giles Charlier, who had several public disputations with the Táborite Bishop Nicholas of Pelhřimov.[178] In reading those pages of The Net of Faith that deal with the Council of Basel we cannot but be impressed by Chelčický’ s deep shock and holy wrath at the double ethic of men who were supposed to represent western Christendom. And we realize more clearly the urgent necessity of Reformation. With all the faults that Chelčický saw in Hussitism it still was a clean current in the midst of the stagnant waters of medieval Christianity. Its representatives alone insisted on the removal of the several hundred prostitutes from Basel during the council session. And it was Giles Charlier who took upon himself the task of defending the presence of prostitution in Basel.[179] In its defense he used scriptural references as well as such authorities as St. Jerome and St. Augustine.[180]

The old saints, in their concern for the well-being of the communities, provided them with legality concerning harlots, so that a town, suffering from lustfulness, might be relieved of it by communal prostitutes. This the Master Aegidius confirms with the help of Church Doctors![181]

The learned men of Basel and the Church doctors may know a great deal, said Chelčický, but they know nothing about a Christian life “lived in perfection and in accordance with the law of God.”[182]

He little respected the Church doctors and saints used by the Romanists to bolster up their patristic edifice of power. Albertus Magnus, the most respected medieval authority of ecclesiastical learning, he called “that loudly howling Albertus,”[183] and he was not much more flattering to St. Augustine to whom he often referred to as “that pillar standing in Rome.”[184] He felt that it was St. Augustine who was the most responsible for providing the Roman Church with a theology of ecclesiastical imperialism:

That great pillar of the Church of Rome which supports her strongly that she may not fall, gave to the gospel the spirit of a sharp sword…[185]

But the greatest sin the Church has committed is her alliance with the state and with the secular methods of power,[186] institutionalism,[187] and coercion.[188]

The Church of Rome has allied herself with the state, and now they both drink together the blood of Christ, one from a chalice, and the other from the ground where it was spilled by the sword.[189]

The Christians have fallen short of the ideal and the only remedy is to obey the Inner Light that comes of the grace of God.

The founder of the German Reformation has written somewhere that man could change but that only God could better. But oddly Luther – the son of a peasant – failed to explain why God worked so exclusively on the side of the ruling classes. Chelčický – the son of a nobleman, if the Záhorka theory proves correct – insisted that the devil rather preferred working with the ruling noblemen and churchmen!

…The pagans do not have … to contend with so many lords and useless clergymen who all hold great dominions… Yes, they do not bear their sword in vain, they rob and oppress the poor working people.[190]

The nobility and the priesthood have “alienated the people from God.” Naturally, Chelčický did not accept Wyclif’s division of men into three estates (noblemen, priests, and the working people).[191] Such division, said he, amounts to an enforced grouping of men into the following professions:

The estate of the ruling class which conducts defensive warfare, kills, burns, and hangs; the estate of the common and higher priests who pray; and the estate of the common peasants who must slave and feed the two upper-class insatiable Baals.[192]

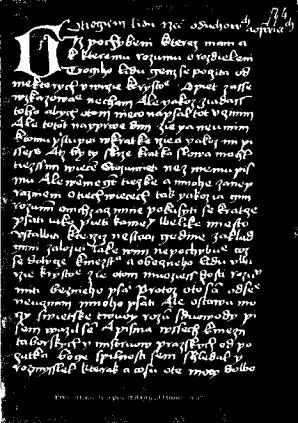

The First Page of the Manuscript About the Three Estates by Peter Chelčický

(This document is preserved in the Library of the Metropolitan

Chapter of Prague, in the Codex “D.32” on folios marked 74a-103a.

It may represent Chelčický’ s own handwriting.)

This division is contrary to the law of Christ and only leads to further evils.

Today authority is a sweet affair to the king opulent with fat and licentious in living … to whom the word “peasant” is repugnant… But woe unto him when he shall meet the words of God face to face! Then his violences shall be met with great discomforts to his well-being, and he shall cry blind, “Alas! Woe is me! Why has my mother ever begotten me into this world!”[193]

To divide Christendom into classes is tantamount to dividing the body of Christ.[194]

Naturally, this order is agreeable to the first two classes who loaf, gorge, and dissipate themselves. And the burden for this living is shoved onto the shoulders of the third class which has to pay in suffering for the pleasures of the other two guzzlers – and there are so many of them![195]

There are many eloquent passages that show that Chelčický was far ahead of his time with his strong social consciousness:

And if you who are heavy and round with fat object saying, “Our fathers have bought these people and those manors for our inheritance,” then, indeed, they made an evil business and an expensive bargain! For who has the right to buy people, to enslave them, and to treat them with indignities as if they were cattle? … You prefer dogs to people whom you cuss, despise, beat, from whom you extort taxes, and for whom you forge fetters … while at the same time you will say to your dog, “Setter, come here and lie down on the pillow.” Those people were God’s before you bought them![196]

Wyclif’s sanction of the old threefold division only perpetuates the old evil that Christ came to abolish. He came to make men free:

(He) bought this people to himself – not with silver and gold – but with his own precious blood and terrible suffering… The heavenly Lord redeems and buys the people for his inheritance. And the earthly lord buys them in order to (enslave them).[197]

God’s wrath will terribly punish the ruling upper class that abetted social exploitation:

Look, you fat one, what a sodomitic life you have prepared for your people! What will you say on the Day of Judgment when the Lord will seat Himself on the judgment throne, and when all injustices committed against this people – yes, the very people which He Himself bought with His blood – will be arraigned against you? And He will say to you, “As you did it to one of the least of these my brethren, you did it to me. Go to hell!” And no high titles, no archives, no records, no documents with seals … will save you from perdition.[198]

Chelčický’s socialism is not a dialectic materialism; to speak figuratively, he stands on firm Biblical ground and examines his contemporary society with a strong searchlight of Christ’s ethic. What he finds is devastating, and his conclusions are more radical than those of Marx or Lenin. Christian faith is dead unless it can show fruits of its existence.

For faith apart from works is dead, useless, and devilish; real faith is alive, useful, and Christian.[199]

His communism is thoroughly Christian, springing from a theocentric view of life:

The earth is the Lord’s and its fullness, that is, its mountains and valleys and all regions… Who is not God’s, has no right to possess or to hold anything that belongs to God, unless he has taken possession of it illegally and by violence. Thus, contrary to the divine law, our fathers bought and established illegal claims for us … and this is our natural heritage: poverty, shame, and death… But God shall regard all these unlawful property holders as traitors of the Kingdom of God.[200]

True followers of Christ obey the commandments of God, love their neighbors as themselves,[201] and cannot therefore take part in any unjust “manner of pagan rulership.”[202]

Luther weakened the foundation of the Church by strengthening the fortifications of the state; Chelčický proclaimed that both the Church and the State were built on quicksand, and that all earnest Christians must build a new society on the firm foundation of “Christ’s law of love.”[203]

“If a murder is committed privately it is a crime, but if it happens with state authority, courage is the name for it.” Chelčický echoed these words of Cyprian[204] with the whole being of his personality. Basing his conviction on Christ’s teaching he fully adopted the position of the early Church Fathers and in many ways anticipated Tolstoy and Gandhi in trying to seek the source of war.

“The sword separates the Christian from God,” he wrote in The Net of Faith.[205] In the sight of God, war is always murder. What is the beginning of wars?

Their root is in intemperate self-love and an immoderate affection for temporal possessions. And these conflicts are brought into this world because men do not trust the Son of God enough to abide by his commandments.[206]

Covetousness and lust for power are the cause of every war. Cain was surfeited with pride of possessions; for this reason he was the first to fortify a city,[207] since it is inevitable that possessors always have to think of aggressors.

The lords try to embrace as much of the earth as they are able, using every means and every ruse or violence to get hold of the territory of the weaker, sometimes by money and at other times by inheritance, but always desiring to rule and to extend their realm as far as they can.[208]

“Death sits in the shadow of authority”[209] which exercises its power contrary to Christ’s will[210] and a Christian has a duty to resist it. An arrogant state authority is a trap for good Christians; it compels its subjects to go and do every evil it can think of.[211] Christ’s death established a covenant relationship between man and God that outlawed war forever.[212] Military service and conscription are “compulsory sins”[213] and to obey the call issued either by the state or the Church is tantamount to honoring sin and the devil.[214] The conscripted men

run to war doing to their neighbors that which God has forbidden and which would not be tolerated at home. The commandment of God says, “So whatever you wish that men would do to you, do so to them.” But he who goes to war does evil to them of whom he would wish that they do good to him; and what he would be loath doing at home, that he gladly does obeying the orders of his lords.[215]

The true followers of Jesus would rather be martyrs than be accomplices in war:

They would refuse to storm the walls, to run like cattle, to destroy, to murder and to rob; instead, they would rather perish under the sword than to do these things so revolting to the law of God.[216]

True Christians must obey their authorities passively and pay their taxes, but active participation is incompatible with Christian virtues.

Man is possessed by the possessions he has. A Christian should not be a slave of material things.

A pagan fights to protect his rights and his property in court or in field; a Christian conducts his life with love, patiently enduring injustice, as he will be rewarded by an eternal gain.[217]

A Christian must abstain therefore from courts and lawsuits. And it goes without saying that capital punishment contradicts the law of love.[218] The priests who support the state authority in its “right” to conduct wars and enforce justice by capital punishment

are making God as having two mouths, with one saying, “you shall not kill,” and with the other, you shall kill.”[219]

God is the sovereign, the Pantokrator,[220] and all human sovereignties, states, and possessions are as nothing in His eyes:

Who becomes acquainted with the law of God cannot create nor recognize nor obey any other law, for no other law is right.[221]

God is love.

Peter Chelčický’s Net of Faith does not read as easily as the Praise of Folly by Erasmus of Rotterdam; it is the product of a man who did not have a formal education that the other absorbed in abundance. We often notice at the beginning of chapters that he meets difficulty in going into the medias res; he is redundant, at times cumbersome, but once he warms up to his subject, he can write passages of rare beauty and spiritual insight. He is not afraid of using homespun turns of speech or afraid of calling a spade a spade.

His life on the farm in Chelčice is reflected in many illustrations taken from the agricultural environment:

Many a king does not know the King of Heaven, but he still is like a plough in the hands of the plowman.[222]

This world that seeks God on the surface is like a goat gnawing the outer bark of a willow; the power and aliveness of faith is hidden from it.[223]

(The Pope) was grafted by the Emperor onto the tree of pagan rule in order to enjoy a most exalted priesthood, and everything stemming from the grafting of this tree is supposed to be more worthy of respect.[224]

Chelčický is no introvert when writing; especially when carried away by his righteous indignation of social injustices or ecclesiastical stupidity and hypocrisy; he does not mince his words and often uses harsh expressions:

(The Pope) seldom celebrates mass, never preaches, and never works; that is, the only work which he instituted for himself is the blessing of those whom he loves and the excommunication of those he does not love. And so he lies in luxuries and gorges himself like a hog wallowing in a sty.[225]

And all this (decadence) has been smuggled into faith with the pagan rule, like an evil smelling corpse, to the great defilement of faith…[226]

The Net of Faith is full of vivid illustrations of the medieval life and is most descriptive, especially in the second volume. That section, from the literary point of view more interesting in many respects, is not included in this thesis because it is an elaboration of the main philosophy presented in Book One.

In the Czech original, The Net of Faith represents a gem of medieval Bohemian literature, excelling in originality of style, purity of expression untouched by foreign affectations, masculine straightforwardness, and occasional tenderness that brings him very close to an authentic mystic expression:

“If any man wants to come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me.” And if your physical will does not want it and rebels against it, compel it yourself. You yourself must rebel against your unwilling will and follow reason. Deny yourself; cling to God through grace, fulfilling His good will by emptying your own ill-will, for the love of God your Lord![227]

Throughout the book Brother Peter of Chelčice speaks to us with a great urgency; let us listen to him, for the Burden of the Lord is upon him. “Woe unto those who are at ease in Rome and in Prague,” cries the Amos of Bohemia; yet, throughout his message there is a warm undertone of ever-present Divine love. It is this undertone that gives The Net of Faith its true grandeur and a relevance for our own “misguided and distraught times:”

Our faith obliges us to bind wounds, not to make blood run.

AMEN

[106] R. Holinka, Traktáty Petra Chelčického…, p.21; Emil Smetánka, ed., Síť víry, Prague, 2nd ed., 1929. p.vii; concerning the dating, cf. Goll in Časopis českého musea, 1881, p.16, and by the same author, Quellen und Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der Böhmischen Brüder, vol.II, p.68 (Prague, 1882); a clue to the dating is found in the Net of Faith, page 73, (“…for the squires would like to have a foreign king, a rich German, who would add alien countries to his own…”).

[107] Spinka, op. cit., p.289.

[109] Straub and Keller, Hortus deliciarum, pl.xxiv, quoted by Emile Mâle, infra.

[110] Can you draw out Leviathan with a hook, or his tongue with a cord which you let down? Can you put a hook into his nose, or bore his jaw through with a thorn?…

[111] Migne, ed., “Patrologiae cursus completus,” vol.76: Sancti Gregorii Moralium libri in Job, col.489.

[112] Migne, ed., “Patrologiae” vol.133: Sancti Odonis … Moralium libri xxxv, p.490, D: … Sed Leviathan iste hamo captus est, quia in redemptore nostro dum per satellites suos escam corporis momordit, divinitatis illum aculeus perforavit. Hujus hami linea Christi est genealogi… Sicut per nares insidiae, ita per circulum divinae virtutis omnipotentia designator …

[113] Migne, ed., “Patrologiae” vol.164: Brunon d’Asti, In Job, p.685.

[114] “Léviathan, le monstre qui nage dans la mer du monde, c’est Satan. Dieu a lancé la ligne dans cette mer. La corde de la ligne, c’est la divinité humaine du Christ; le fer de l’hameçon, c’est la divinité de Jésus-Christ; l’appât, c’est son humanité. Attiré par l’odeur de la chair, Léviathan veut le saisir, mais l’hameçon lui déchire la mâchoire. (Quoted in the great work on medieval art, L’art religieux du XIIIe siecle en France, by Emile Male, Paris: Armand Colin, 6th ed., 1925, pp.384 et sqq. Coulton remarks that this symbolism is one of the medieval methods of explaining the Atonement to the popular mind, and “that it ranks side by side with that other simile, immortalized by the great schoolman Peter Lombard (Sent. III, dist.xix,a), that God made a mouse-trap for the devil and baited it with Christ’s human flesh. (G.G.Coulton, Art and the Reformation, New York, Knopf, 1928, p.298. The symbolism is portrayed on the miniature of the Hortus deliciarum is reproduced here.

[115] Cf. F. M. Bartoš, Hledání podstaty v české reformaci (Seeking of the Essence of Christianity in the Czech Reformation), Prague: Kalich, 1939, p.4, n.9.

[117] Regnabat 306-337.

[118] Regnabat 314-336.

[119] R. G. D. Laffan, Select Documents of European History, London: 1930, vol.I, pp.4-5. The legend of the Donation was pictorialized about the year 1250 in ten murals of the oratory of St. Sylvester near the Church of Santi Quattro Incoronati on Monte Cello, Rome. (Cf. Archivio della Societá romana di Sta.Patria, Rome, 1889, p.162).

[120] The Pseudo-Isidorian Decretals consist of two parts; the first part contains about 60 epistles of popes, beginning with St. Clement (circa A.D. 95) and ending with Melchiades (314) (page 78), and for the most part professedly addressed to all the bishops of the Church Universal. The epistles ascribed to Clement are ancient forgeries, and the remainder of the decretals are false documents issuing from the school of Boniface in Metz, and were first published by one Isidore Mercator, circa A.D. 850, being at once accepted in Rome and made part of the body of the pontifical law. (Littledale, The Petrine Claims, London: 1889, p.347). The second part consists of papal decrees of the period between Sylvester I (regnabat 314-336) and Gregory II (regnabat 715-731) of which 39 are spurious, and of the acts of several councils which are quite unauthentic. It opens with the Donation of Constantine, the most famous of all these forgeries, parts of which were quoted in the text above.

[122] Rinaldi records (Annales IX, p.l45), that Emperor Sigismund of the Constance Council fame was crowned Emperor by Pope Eugenius IV only after he had re-confirmed and ratified the Donation of Constantine.

[123] Nicholas of Cusa, De concordantia catholica, A.D. 1435, (cf., Girolamo Mancini, Vita di Lorenzo Valla, Firenze, 1891, pp.l45ff). Another clergyman who doubted the authenticity of these documents was Reginald Pecock, the Bishop of St. Asaph, who wrote in 1444 The Repressor of Over-Much Blaming of the Clergy (reprinted in London in 1860, cf. p.350-366); cf. Marsilius of Padua, Defensor pacis, dictio II, cap.11; Dante: De monarchia, III, 10.

[124] Vivebat 1405-1457. Of course, Valla immediately had many enemies who wrote against his discoveries, but in vain (e.g. Antonio Cortesi di Pavia, Antivalla, etc.). It is significant, however, that Valla’s discovery was reluctantly recognized as valid by the Church of Rome only 430 years later, on September 20, 1870! (Cf. Mancini, op. cit., p.157).

[125] A.D. 313. Again, legend has it that Constantine granted the Edict of Toleration to the Christians after his miraculous victory at the Milvian Bridge.

[126] Lewis Mumford, The Condition of Man, New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1944, p.70.

[127] The Net was written circa 1440-1443 and the Declamatio in 1440. This represents another example of the phenomenon which Toynbee calls “simultaneous pluralistic creation” (Study of History, vol.III, p.238). If we tried to explain this incident on the basis of Toynbee’s interpretation of history as yin and yang we might say that the challenge presented by the bankruptcy of official Christendom to the stricken and stunned population of the nations of the Holy Roman Empire was taken up by these two men; both men were launched by their parents on the conventional career of their society and class and generation; both showed their creative genius in rebelling against the outworn convention. Both brought their genius to fruition by withdrawing: Valla by leaving Rome and going to Pavia and Florence; Chelčický by leaving Prague and the Táborites and going to the hamlet of Chelčice. In their retreat they disentangled themselves from the trammels of society in order to return in due course with a new moral power and a new practical policy for dealing with a new state of affairs to which the old order had no application. Cf. Toynbee’s chapter “Analysis of Growth,” op. cit., vol. III, pp.217-377.

[128] Page 89, Peter Kropotkin, The Conquest of Bread, New York: Vanguard Press, 1927, p.17.

[129] Page 102, (Judges 8: 22-23).

[130] Page 93, page 140, l Samuel 8:4-20 and 12:18-19.

[133] Page 101, 1 Kings 12:11.

[138] Chapter 30 et passim.

[139] Page 95. Transcriber’s note: some of Molnár’s references seem a bit weak to me, but I have preserved them as they are.

[143] Chapter 30 et passim.

[164] NF, book I, chapters 6-12.

[166] Page 25, page 30, page 73.

[174] A.D. 1431-1449.

[175] NF, book I, chapters 13-18.

[191] NF, book I, chapters 30, 28, et passim.

[204] Epistles I;6.

[220] From the Greek pantokratoros, meaning ‘all powerful’.