THE NET OF FAITH

by Peter Chelčický

translated by Rev. Enrico Molnár

I see no good in having several lords;

Let one alone be Master, let one alone be King.

– Homer

The curious case of Peter Chelčický is one of the much covered-up mysteries of the history of the Church and / or religious thought, in spite of the fact that “his works of outstanding quality in contents and in composition … rank among the most precious manifestations of the Czech spirit.”[26] He has passed by acclamation into the company of the great philosophers of the Christian community on the strength of a total of some forty theological writings, and more particularly on the strength of his crowning magnum opus, The Net of Faith.

We know exceedingly little about him beyond what his writings and the correspondence of his contemporaries as well as what some of their oblique references disclose; though scholars have searched incessantly during the past three decades for any scrap of further information concerning so notable a figure.

There has been much conjecture as to where and when Peter Chelčický was born. There are two general theories. Until recently, the consensus of scholars was that the date of his birth should be sought in the year 1390 – or possibly sooner – but definitely not later.[27] In other words, he was supposed to have been born sometime in the middle of the reign of King Václav IV of the Luxembourg Dynasty.[28] According to this theory, his birthplace is to be found in Chelčice, a village not very far from Vodniany and Husinec (the birthplace of John Hus) in the region where, fifteen decades before, Peter Waldo presumably died. To his friends he was known as Brother Peter; and if this theory is correct, he began to call himself “Chelčický”[29] after the village of Chelčice only in his thirties.

Quite recently Dr. F. M. Bartoš of the Hus Theological Seminary in Prague has come out with a new theory.[30] Recalling the historian Palacký’s hypothesis that Chelčický was a yeoman, Bartoš seeks to trace him in the documents relating to the country nobility, for only such background would explain the personal independence that Chelčický enjoyed, not being compelled to perform manorial duties. As far as we know, Chelčický never signed his works, and his name appears only later, on the printed volumes of his Postilla and The Net of Faith, that is, in the years 1522-1532, which is quite some time after his death. Master Přibram calls him, in 1443, simply “Peter.”[31] The appellation “Peter Chelčický” was possibly created by Brother Gregory of the Unitas Fratrum who visited Peter, toward the end of his life, in Chelčice.[32] These considerations make a tabula rasa for the daring new theory of Bartoš who writes that Chelčický’s original name may have been Petr Záhorka. His father was Svatomár of Záhorčí who claimed Hrádek Březí near Týn above the Moldau as his ancestral castle. This Peter was born sometime between 1374-1381. The documents describe him as a mild-mannered nobleman of a peaceful character who was not opposed to the secular legal order, “and it is worth noticing that Peter (Záhorka) joined the Táborites during the revolution… Peter Záhorka ceases to be mentioned in our sources after the year 1424 when he would have been at the most fifty years old… But the disappearance of the news about Peter Záhorka could be also explained in this way, that his following existence continued in the life of Peter Chelčický.”[33]

If the hypothesis of Dr. Bartoš is correct, then we would venture to suggest the following reconstruction. The young ‘Chelčický’ was a scion of a family interested in politics and church life; this would explain a certain cultural maturity of the environment. He became orphaned in his early youth, thus losing a greater part of his inheritance. He was contemptuous of the customary career of his contemporaries and refused to enter the services of either the nobility or the Church, choosing instead to serve the people whom he wanted to educate.

If Chelčický were really Peter Záhorka, we would gain a valuable aid for the solution of the question as to when and how he arrived at his conclusions about the basic discrepancy between the principles of Christianity and the principles of the state. For, as we well know, he developed this theory … only sometime around 1425 in his tract About the Threefold People.[34]

The question of his occupation is not yet definitely settled either. The historian Šafařík thought that Chelčický was a priest,[35] Lena assumed that he was a member of the Waldensian Church and even of a Waldensian family; later sources identify him as belonging to the cobbler’s trade; other guesses range from regarding him a serf to a squire.[36] On one occasion, Chelčický calls himself a peasant. This was often interpreted literally but

it is hardly possible to think of him as a serf. Sedláček already sought him among the noblemen of Chelčice, while Chaloupecký argued that the views, peculiar knowledge, and traditions manifested in the writings of Chelčický identify him as belonging to the class of country squires.[37]

This only corroborates the hypothesis of Bartoš. All available evidence seems to point in the direction of such a conclusion. In discussing Chelčický’s special position, Professor Spinka writes:

Judging from his obvious sympathy and identification of himself with the common people, it seems fairly safe to assume that he was one of them; for had he been a serf, he would not have been free to go to Prague to study and later to devote himself to his literary work of religious reformation as he did.[38]

Chelčický had no regular academic education; many of his adversaries took advantage of this fact reproaching him that he “not a priest, mingled into questions pertaining to priests only”; another shocking fact perturbed his more academic adversaries, namely, that he did not write in Latin, and what was worse, that he knew only the rudiments of that language! But he was humble in spirit and frankly confessed, “I can give but meager and weak testimony concerning Latin.”[39] The editor of the Vilémov Edition of The Net of Faith (1521) reminds us that “there are many who do not slight Chelčický just because he is a layman and not learned in the Latin tongue”; on the contrary, he emphasizes that

though he was not a master of the seven arts, he certainly was a practitioner of the eight beatitudes and of all the divine commandments, and was therefore a real Czech Doctor, versed in the law of the Lord without aberration from the truth.

It is entirely possible that Chelčický studied in his youth in some monastery where he may have acquired an elementary knowledge of Latin.[40] Whatever his academic background may have been, his correspondence and writings reveal that he was by all standards a man thoroughly acquainted with the crisis of his time and with the thought of the leading spirits of the contemporary scene, as well as with the literary heritage and history of the Christian Church.

Southern Bohemia where Chelčice is situated had been for quite some time the cradle of many men outstanding in religious thought of the fourteenth century, such as Matthew of Janov, Thomas of Štítný, Adalbert Raňkov, and others. It was a region “infested with Waldensian heresies,” which found open doors of hospitality in the homes of humble peasants and small yeomen.

As to the physical aspect of the region, even today the voice of Southern Bohemia is rather on the quiet side; inarticulate, low-pitched, prone to the expression of humorous doubts and biting skepticism, rolling like the hills and meadows of the unpretentious countryside. There is nothing grandiose about this landscape: no snowcapped mountains but only furrowed fields, no broad rivers but only quiet brooks and placid lakes reflecting the skies.

Such is the region where – perhaps – Chelčický was born and where he certainly spent the latter part of his life. He seems never to have quitted Bohemia for a day during his seventy (or ninety) years of life; he went several times to Prague (where he may have heard John Hus), to Písek, and probably once to Kutná Hora. The excited social and political activities of these cities left him unmoved, and he gave greater preference to the contemplative solitude of Chelčice.

Among the earliest sources of Peter’s knowledge were the writings of Thomas of Štítný.[41] Their study left a deep imprint in Chelčický’s spiritual life. Štítný’s works, written in the vernacular, introduced him to the intellectual world of the Middle Ages, and the author’s religio-ethical essays encouraged his alert mind to ponder and meditate over the basic Christian truths, to compare the ideals of the Church of the days of the Apostles and Fathers with the realities of the Christian Society of his own time, and to come to rather distressing and uncomplimentary conclusions.

The other three great influences on the intellectual development of Peter were John Hus, John Wyclif, and the Waldensian tradition. It is still a mooted question whether Chelčický ever met Hus in person[42] but this we know for sure: he was thoroughly conversant with the writings of the great Czech reformer. Similarly, he knew the teachings of Wyclif with whose thought he became acquainted through various translations and extracts published in Prague as well as through the polemical literature flowing in abundant profusion from the pens of Hussite priests. And as to the third influence, “Waldensian heresies were rampant” all over southern Bohemia. In his opposition to Hussite formalism Chelčický could not but feel sympathetic toward the Waldensian teachings that urged a return to apostolic simplicity.[43] In the following chapters we shall see how these ideas permeate his philosophy.

But Chelčický was not a copyist. Far from that. He accepted from Štítný, Hus, Wyclif, and Waldensianism what he thought to be sound and biblically correct; that was his starting point. But from there he went on quite independently, basing himself solely on the Bible. He disagreed with Štítný, who thought that a mere reform would do away with social injustices. “You cannot improve society without first destroying the foundations of the existing social order,” insisted Chelčický. He felt a deep respect for Hus, but he rejected with harsh words his unbiblical notions of purgatory, his views on war, oaths, and the worship of pictures.[44] He loved Wyclif but he rejected his traditional – can we say, ‘undemocratic’? – division of men into three estates (lords, priests, and the working people). He felt very close to the Waldensians, but to him their Christianity was not radical enough. He agreed with St. Ambrose that God has given the earth to the common use of all, and that therefore the rich have no exclusive right of ownership.[45] He retained an astonishing independence of judgment that brought him into personal contact with the leading spirits of the Hussite movement. There is preserved an amazing woodcut of the period portraying Peter Chelčický discoursing on equal terms with the doctors of the Prague University; he had discussions with Master Jakoubek of Stříbro, head of the University, with the Hussite bishops Nicholas of Pelhřimov and John of Rokycana, who was then the Primate of Bohemia, and with the foremost Hussite philosopher Dr. Stanislav of Znojmo.

Peter Chelčický Conversing with the Doctors of the University of Prague

(A photographic copy of a drawing reproduced in Traktáty Petra Chelčického:

O trojím lidu; O církvi svaté, edited by Dr. Rudolf Holinka, Prague: Melantrich, 1940)

His unique position of independent spiritual leadership is attested by the custom that developed among all learned Czechs to send to him their writings or at least extracts of their books, requesting his criticism and judgment.[46] Bishops and theologians journeyed to visit him at his farm in Chelčice or in the more convenient nearby town of Vodniany,[47] and he in turn was invited to attend Táborite or Utraquist church councils at Písek,[48] Kutná Hora,[49] and elsewhere. His farmhouse soon became a refuge and oasis of all free-minded souls. When Peter Payne, the English “Hussite” theologian, was driven out of Prague after the restoration of Emperor Sigismund, he was welcomed in the hospitable solitude of Chelčický’s home.[50]

Of course, Chelčický was sought by these philosophers and theologians only after he had established his reputation as an independent thinker in 1419 when many of the more radical Hussites, the Táborite priests, impatient with the coming of the Kingdom of God “beyond history” and restive under chiliastic hopes, began to realize the Kingdom “in history” with sword in hand.[51] It was then that Chelčický made public his first disagreement with the official position of Táborite Hussitism. We shall deal in the next chapter with the history of his estrangement from the Hussite movement; however, 1419 marks a decisive turn in Chelčický’s life and deserves a closer study.

In that year it became apparent that an armed conflict between the supporters of Rome and the followers of Hus was inevitable. Together with other travelers from southern Bohemia, Chelčický went to Prague to take part in a popular gathering held in a place called “na Křížkách.” When we examine the records of this gathering, which bears all the earmarks of a popular referendum or town-hall meeting, we cannot but be impressed by the concern the delegates of southern Bohemia felt about the whole question of justification of war. They asked whether it is permissible for Christians to attack an enemy “if necessity arises.” The questions were addressed to the Masters of the Prague University – then a stronghold of Hussite learning. The Masters were decidedly embarrassed by such ill-timed questions. Jakoubek of Stříbro, the rector of the University and spiritual leader of the Hussite movement after Hus’ martyrdom, answered on their behalf in the affirmative, imposing the condition that “all cruelty, avarice, and all iniquity and excess be eliminated.”[52] Chelčický was not satisfied, with this ambiguous answer. After the meeting he called on Jakoubek in his apartment near the Bethlehem Chapel, asking him to give scriptural evidence from the New Testament supporting war “short of cruelty and avarice.” Jakoubek could supply no such “proof from the Gospel”;[53] he was able to appeal only to the authority of the Church Fathers and to Thomas Aquinas’ doctrine of the righteous war,[54] a doctrine that sanctions war if it meets the three conditions of causa iusta, auctoritas principis, and intentio recta.[55]

Chelčický found the arguments of Jakoubek unconvincing and the doctrine of Thomas Aquinas[56] unacceptable. Chelčický became a nonconformist when he declared, “God never revoked His commandment ‘You shall not kill’.”

This reply is striking in its simplicity, consistency, and moral logic. In it Chelčický aligns himself with the traditional early Christian position of thorough pacifism. He takes up the absolutist stand of Tertullian who asserted that “Christ in disarming Peter unbelted every soldier.”[57] Chelčický was utterly disgusted with the dualistic ethic of Jakoubek and his fellow theologians of the Hussite Reformation, a dualism which anticipated formally and emotionally the principles adopted in 1643 by Cromwell’s Ironsides, a dualism which tended to make the temporal power brutal and the spiritual power irresponsible, a dualism which gave its sanction to a special ethic for the civitas Dei[58] and another for the civitas terrena.[59]

Jakoubek became incensed by Chelčický’s “obstinacy” and in 1420, when Emperor Sigismund declared war, which Pope Martin V seconded by proclaiming a crusade against “the Wyclefites, Hussites, and other heretics, their furtherers, harborers, and defenders,” the masters of the University fully endorsed Jakoubek’s Thomistic sanction of the “just war.” It was on this occasion that Peter parted with the Calixtine leaders.[60]

On both sides, papal and Hussite, war became not only outwardly but also ideologically a crusade.[61] Hussitism was transformed into a reincarnation, as it were, of the primitive Hebrew concept of the Warrior Nation fighting the battles of its War God Yahweh. It was quick, violent, and single-minded as are all true mass revolutions under which the old order crumbles to dust. And it was a crusade for Yahweh. For “a revolution always has this in common with a crusade: that it is fought not under but against the authority of the prince. A war fought primarily for the defense of an ideal tends to be a crusade, especially if that ideal is religious.”[62]

Hussitism proclaimed (allegiance) with the old Hosts of the Lord and against the violence of evil forces set violence for the good. An eye for an eye! The name of Jesus – the Prince of Peace – was sung by the thousands of warriors of Hussite columns with a fervor almost unheard of for fourteen hundred years, and the hands of the same people were still warm and red from the blood of the enemies of the Law of God:

So then, archers and lancers of knightly orders,

Halberdiers and scourge-bearers of all ranks,

Remember the generous Lord,

Fear no enemies and disregard their numbers.

Have your Lord alone in your hearts,

Fight with Him and for Him,

And never flee before the enemy!…

Shout joyously the war cry:

“Onward ho! Up and at them!”

Hold firm your weapons and cry:

“God is our Lord!”[63]

Chelčický realized with more penetrating insight than any other reformer the necessity for the Church of Christ of resisting identification with any organized company of people, that is, of being in a strict sense the fellowship of the Holy Spirit – the living spring of Christian life. With prophetic perception he revealed and denounced the Hussite tendency of identifying Christianity, the cause of Christ, with the cause of the Czech nation. He saw that to the iniquity of a crusade they added the curse of nationalism. This nationalism began with a sense of exclusion, or “manifest destiny,” and ended with a desire for domination.[64]

The fusion of the “sour ferment of nationalism” with the “new wine of democracy” in the “old bottles of tribalism,” to use Toynbee’s terminology, produced amazing immediate results. The Hussites, under the remarkable leadership of the warlord Žižka[65] (who shares with the Timurid Emperor Babur of Northern India[66] the dubious honor of inventing the fortified chariot that anticipates our modern tank) defeated the Imperial Crusaders’ international brigades in two bloody battles near Prague.[67]

Peter Chelčický’s spiritual maturity and greatest intellectual activity coincided with these years of Czech military glory, the Hussite armies were fighting victoriously against almost all European nations[68]; the fear and fame of these ‘warriors of God’ were so great that by the mere singing of their anthem[69] they drove away the strong forces of crusaders sent against them (Julian Cesarini, the Papal Legate who later became famous at the Council of Basel, being on one occasion in such a hurry that he lost his purple mantle, his crucifix, and the pontifical bull, near Domažlice). Chelčický remained unswayed by the elation of the other Czechs joyously marching to the tune of their martial hymn, thinking they were establishing the Kingdom of God on earth. He severed his connection both with the masters of the Prague University and with the Táborites, and retired to his farm in Chelčice. He chilled the enthusiasm of the Hussites by telling them they were not a whit better than common murderers. To Žižka’s fighters as well as to the University’s scholars his Christian protest sounded like a discordant note in the martial strains of their anthem. Yet this did not deter Peter. He set himself apart from the national revolution and from the great struggles within the Hussite movement, concentrating all his efforts on the purification of the spiritual revolution started by John Hus. After his withdrawal to Chelčice he began his life mission to “enshrine his thoughts in works that rank among the most precious treasures of Czech literature.”[70] In all of them, regardless of their topic, he kept on reminding the followers of Hus that they cannot bring about the Kingdom of Heaven as long as a hell of hatred burned within their hearts.

In all of his writings we recognize his great debt to the men he admired: Wyclif, Hus, and Štítný. But he went further than any of these. In accordance with the Waldensian teachings, Chelčický proclaimed that the taking of life in any form, even in war, was sin, and that whoever killed a man in battle was guilty of “hideous murder.”[71]

He felt the burden of the Lord and His Word was upon him and he looked at the Hussite affairs and the affairs of the world through the eyes of the Bible. Focusing his attention to the Kingdom which is not of this world, Chelčický returned time and again to the kingdoms of men, and not even the most modern and most daring thinkers ventured to postulate with such relentless and thoroughgoing logic the claim of the sovereignty of the rule of God over the affairs of the human society as did the wizard of Chelčice.

In the books which he began writing at his country retreat we sense a passionate popular protest against the cruel moral irresponsibility of the Hussites dependent for their intellectual priming on nothing more reliable than university professors suffering from acidosis of the head and heart, and against the similarly cruel ignorance of the crusaders who depended for their ethical balance on the immaculate perception of the Pope of Rome. He wrote these protests in a popular style often circumlocutious, sometimes involved, but always of such a quality that they remain “among the few medieval literary works which can even today captivate our interest."[72]

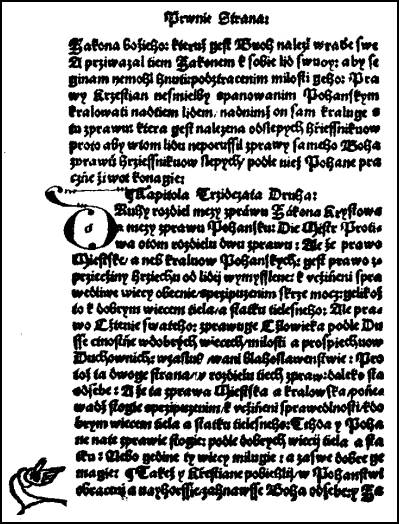

A Printed Page from the 1521 Edition of The Net of Faith

(The section shows the beginning of the thirty-second chapter. At the end of the second line and beginning of the third line are the words “Mistr Protiva” – i.e. the “Master Adversary” – which stands for John Wyclif.)

Because of his high moral integrity and new approach to Biblical Christianity he gathered around himself a small group of loyal followers who were called the “Brethren of Chelčice.” They distinguished themselves by being absolute pacifists who, by their insistence on unconditional obedience to the commandment “you shall not kill”, dissociated themselves entirely from the patriotic Hussite wars; they refused to sanction capital punishment, to make oaths, and to accept any government position, thus in many features paralleling the Rhinelandish Brethren of the Free Spirit, the Dutch Brethren of the Common Life, the Mennonites, the Fratricelli, and anticipating the British Quakers.

In 1434 there occurred an event that led indirectly to the foundation of the Moravian Church or, as it is more accurately called, the Unity of Brethren: the Battle of Lipany. In this great fratricidal battle of the two Hussite factions, the radical Táborites were defeated by the moderate and aristocratic faction of the Utraquists. The consequence of this tragic event was a general religious tiredness and torpidity. The moderate Utraquism did not muster enough courage to settle accounts with the Church of Rome or to eradicate abuses within its own ranks of clergy. The Utraquist Archbishop, John of Rokycana, preached vehemently against this degeneration of the movement; he soon had the following of a small group of young men who strove after a purified Church life. These earnest seekers asked the Archbishop[73] to advise them what to do in order to accomplish this reform. Jan Blahoslav, the historian of the Czech Brethren, recorded in 1547 Rokycana’s answer:

Then Master Rokycana showed to those who were with him – which is to say, to Brother Gregory and other companions of his – the writings of Peter Chelčický, (admonishing them) to read these books which he himself often perused, especially since Peter Chelčický had written some of them especially to Master Rokycana. Obeying his advice the brethren read the books of said Peter Chelčický with much diligence. Yes, they even had many talks with him… And as soon as they saw again Master Rokycana they thanked him for his advice, and also, that they made very good use of it, they told him.[74]

By this time Chelčický had already established his reputation as an independent thinker; in addition, he and Rokycana had exchanged a number of letters in which they discussed matters of ecclesiastical discipline, sacraments, and articles of faith. Even though they did not see eye to eye on many points, Rokycana – at that time, anyway[75] – respected Chelčický’s views, hence his recommendation to the young reformists to get in touch with the philosopher of Chelčice.

We do not know what Brother Chelčický spoke about with Brother Gregory and the “other companions of his,” but we know that the result of these conversations was the establishment of a religious community on the estate of Castle Litice in the Eagle Mountains of northeastern Bohemia. This estate was a personal property of a Hussite nobleman, George of Podiebrad, who had just then become King of Bohemia.[76]

(Gregory and the brethren) asked Rokycana to plead for them with the King that he might give them a place to live on his estate of Litice, in the village of Kunvald behind Žamberk. He granted their request and so many of the faithful gathered there…[77]

Kunvald became the first community of the new growing “mustard seed.” When King George had given them the grant, there gathered in Kunvald, under the outstanding leadership of Gregory,[78] noblemen and artisans from Prague, and yeomen, priests and peasants from Moravia. All of them, forgetting their provenience and antecedents, began addressing each other “brother.”[79]

Brought together by their common yearning after the “City of God,” they formally founded in 1457[80] the Unity of Brethren, and ten years later, in not far-away Lhotka near Rychnov, the Unitas Fratrum definitively broke away both from the Church of Rome and the Utraquist Church by inaugurating a priesthood of its own.[81]

Peter Chelčický, strictly speaking, did not found the Church of the Unity of Brethren nor any other ecclesiastical organization; never did he become as famous as his older contemporary, John Hus. However, in solitude, and wearied by the atmosphere of strife and hatred, he grappled with the problems of the gospel of Christ with a peasant-like tenacity which overcame all possible educational handicaps; amid the treacherous sands of time he found God who stands still; in the desert places of history he found the inner spring whose waters never fail; and he truly became a voice crying in the wilderness, an Amos of Bohemia who interpreted with audacious consistency the categorical imperative of Christian ethics to harmonize the means with the ends, the conduct of man with the all-pervasive Kingdom of God. He was one of those great individualists to be found in epochal periods, who gather to themselves the influence of preceding ages, and give new direction to the spiritual trends of succeeding generations.

Es bildet ein Talent sich in der Stille,

Sich ein Charakter in dem Strom der Welt.[82]

Chelčický himself was fortunate to live long enough to see the establishment of the Church of the Unity of Brethren; he may fairly well be called the spiritual father and founder of this new church, since it was his influence which was so decisive in shaping the thoughts and acts of the first Brethren, even though he never became an active participant in the founding of the Unity.[83]

The day of his death is shrouded in a cloud of uncertainty, just as his birthday is unknown. He is supposed to have died sometime in 1460, in the days of King George of Podiebrad. With him died a representative of the purest ideals of the Middle Ages, a son of a great time, yet standing far above it. In that rugged expression of Christian faith he is a worthy successor in that noble line of Peters: Peter the Apostle who exclaimed, “We must obey God rather than men,” and Peter Waldo who echoed him and, in pursuing this higher loyalty, dared to deny the man-made allegiance to Rome. We suggest it is no arrogance to place Peter Chelčický in this “apostolic succession” of the aristocracy of the spirit, because in an atmosphere of the despotism of uniformity – whether of the church or state variety – he dared to postulate and define the imperative need of refashioning human economics on the model of the early Church and of Christ’s gospel of love.

Peter Chelčický is great, one of those “who shall inherit the earth,” because he was humble, poor in spirit, and because, surrounded on all sides by the forces of the sword, he dared to break his own.

[26] Kamil Krofta, A Short History of Czechoslovakia, London: Allen & Unwin, 1935, p.55.

[27] Cf. Rudolf Holinka’s introduction to Traktáty Petra Chečického: O trojím lidu – O církvi svaté. Prague: Melantrich, 1940, p.6.

[28] ‘Wenceslas’ (regnabat 1378-1419), son of Charles IV.

[29] The name “Chelčický” is pronounced Khel-cheet-skee, with accent on the first syllable. This name is so intrinsically Czech that it presents almost insurmountable obstacles of pronunciation to non-Slavs. Foreign commentators have mistreated this name as badly as they have mismanaged the name of Wyclif (spelled in 19 different ways). The German translator and biographer Vogl spells his name Cheltschitzki, while the English translator of Tolstoy’s book, The Kingdom God Is Within You, spells it Heltchitzky. The philosopher himself never ventured to Latinize his name as was the fashion of the Middle Ages. In my series of articles, “A Short Prehistory of Moravianism” in The Moravian, vol. 88 (July-August 1943), I used – out of consideration for the American reader – the Latinized: form of “Khelsicus.” In this study, however, we shall avoid all such semantic monstrosities and adhere to the original Czech name, Chelčický.

[30] F. M. Bartoš, Kdo byl Petr Chelčický?(Who Was Peter Chelčický?), reprint from the “Jihočeský sbornik historický” (South-Bohemian Historical Review), Tábor, 1946, 8 pages. Cf. Palacký, Dějiny národu českého. vol.IV, pt.1, Prague, 1875, p.409.

[31] J. Goll, Quellen und Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der Böhmischen Brüder, vol.II, Prague, 1882, p.63.

[32] Acty Jednoty, I, 3, edidit Bidlo, Prague, 1915.

[33] Bartoš has culled much of his information about Záhorka from Aug. Sedláček, Hrady a zámky, (Castles and Manors), vol.VII, Prague, 1890.

[34] Bartoš, op. cit., p.7.

[35] Holinka, op. cit., p.6.

[36] Cf. Lenz, Učení o sedmeře svátostí, p.20, n.2; Holinka, op. cit., p.6-7: Palacký, op. cit., IV, pt.1, p.409.

[37] Holinka, op. cit., p.7.

[38] Matthew Spinka, “Peter Chelčický – Spiritual Father of the Unitas Fratrum,” Church History, vol.XII, 4, p.272.

[39] J. Straka, ed., Petra Chelčického Replika proti Mikuláši Biskupci Táborskému, Tábor, 1930, p.63.

[40] Holinka, op. cit., p.7.

[41] Thomas of Štítný (vivebat 1331-1401?), a nobleman and litterateur. Influenced by John Milič, he became an eloquent preacher and a brilliant religio-ethical essayist. Through the critical study of the Bible he endeavored to discover the ideal Christian life. Desiring to share his discoveries with the larger masses, he wrote his books in the Czech vernacular. To the university professors, his teachers who objected to this practice of his, he replied, “A Czech is as dear to God as a Latinist.” In his books Řeči besední (which could be translated as “Fireside Talks”) and Řeči nedělni a sváteční (“Sunday and Holy Day Sermons”), he interprets the basic Christian ethics and condemns the abuses of the privileged classes. His style is lucid and witty. (Frantisek Götz, Stručné dějiny literatury České. Brno: USJU, 1939, 65th ed., p.7.)

[42] “It was formerly assumed that he must have gone to Prague during the years of Hus’ active service in Bethlehem Chapel and there acquired his knowledge of the Master’s views. But such an inference finds no positive confirmation in the available sources, although it cannot be ruled out dogmatically. It seems more natural to suppose that Peter’s references to his personal contact with Hus should be understood in the sense that he had heard the Bethlehem preacher after the latter’s withdrawal from Prague in 1412, when he had taken refuge in southern Bohemia, in the very neighborhood of Chelčice.” Spinka, op. cit., p.272.

[43] Holinka, op. cit., p.10; also, V. Novotný, Petr Chelčický, Prague: Topič, 1935, p.5 and 14.

[44] F. O. Navrátil, Petr Chelčický, Prague: Orbis, 1929, p.34.

[45] “The superfluities of the rich are the necessities of the poor. They who possess superfluities possess the goods of others. The earth belongs to all, not to the rich. But those who possess their share are fewer than those who do not.” St. Ambrose.

[46] Writings were sent to him for instance by Archbishop Rokycana; Nicholas Bishop of Tábor (De non adorando); Peter Kániš, theologian of a fundamentalist and chiliastic Hussite sect (De existentia vera); John Němec of Žatec; Martin Huska alias Loquis; Markold of Zbraslavice; Martin Lupáč; Master Martin of the Bethlehem Chapel; Jakoubek of Stříbro; and many others.

[47] Novotný, op. cit., p.7; Spinka, op. cit., p.285.

[48] F.M. Bartoš, “K počátkum Petra Chelčického,” Časopis Českého Musea, 1914, 2, p.156f.

[49] František Palacký, Dějiny národu českého, Prague: 1864, p.240 (vol.IV).

[50] Peter Payne, often called “Master English” in Bohemia, was a disciple of Wyclif. Having been expelled from the University of Oxford he went to Prague where, on February 13, 1417 he became professor of the Charles University. He remained in Bohemia until 1452, taking an active part in all theological discussions of the Hussite parties, and generally siding with the more radical elements. (See Palacký, op. cit., IV, p.226). J. Baker, A Forgotten Great Englishman: or the Life and Work of Peter Payne the Wicleffite, London: 1894.

[51] Holinka, op. cit., p.11.

[52] Holinka, op. cit., p.12.

[53] Ibid.

[54] “Ad belli manque rectificationem videntur tria esse necessaria, videlicet iusta vendicatio, licita auctorisacio et recta intencio.” Goll, Quellen und Untersuchungen, II, p.52. See Spinka, op. cit., p.275. footnote 11.

[55] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, II:ii, Quaestio 40.

[56] Thomas Aquinas (relying wholly on St. Augustine, see the latter’s Ep. ad Marcel., cxxxviii; Contra Faustum, xxii:74; De serm. Dom. in Monte, i:19, Ep. ad Bonif., clxxxix, etc.) writes:

In order for a war to be just, three things are necessary. First, the authority of the sovereign is required, by whose command the war is waged. For it is not the business of a private individual to declare war, because he can seek for redress of his rights from the tribunal of his superior… And as the care of the common weal is committed to those who are in authority, it is their business to watch over the common weal of the city, kingdom, or province subject to them. And just as it is lawful for them to have recourse to the sword in defending that common weal against internal disturbances, when they punish evil-doers, according to the words of the Apostle (Romans 13:4): ‘He does not bear the sword in vain, for he is God’s minister, an avenger to execute wrath upon him who does evil’; so too, it is their business to have recourse to the sword of war in defending the common weal against external enemies.

Secondly, a just cause is required, namely that those who are attacked should be attacked because they deserve it on account of some fault. Wherefore Augustine says, ‘A just war is wont to be described as one that avenges wrongs, when a nation or state has to be punished, for refusing to make amends for the wrongs inflicted by its subjects, or to restore what is seized unjustly.’

Thirdly, it is necessary that the belligerents should have a rightful intention, so that they intend the advancement of good, or the avoidance of evil… For it may happen that the war is declared by the legitimate authority, and for a just cause, and yet be rendered unlawful through a wicked intention. (The Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas, Part II, Second Part, translated by the Fathers of the English Dominican Province, London: Burns, Oates, & Washbourne, 1916. First Number, Question 40; vol.9, pp.500-503.)

Some later teachers like Bellarmine and Suarez have added the condition that the war must also be carried out in a just manner, without unnecessary violence and damage. (Cf. A. Vanderpool, La doctrine scolastique du Droit de Guerre, Paris, 1919, p.54.)

[57] De Idolatria, XIX.

[58] “For a priest in person to engage in war, fighting according to the flesh as is seen among many, is against Christ, the Gospel, His life and example, and against the teaching of many of His saints.” Jakoubek’s own words. (F. Šimek, Jakoubek ze Stříbra: Výklad na Zjevení sv.Jana, Prague: 1932, vol.I, p.572, quoted by Spinka, op. cit., p.276

[59] “Warriors who for God are fighting

And for His divine Law;

Pray that His help be vouchsafed you,

With trust unto Him draw.

With Him you conquer,

In your foes inspire awe.”

From the first stanza of the Hussite Anthem “Warriors Who For God Are Fighting.” Cf. Z. Nejedlý, Počátky husitského zpěvu (The origins of the Hussite songs), Prague: 1907.

[60] Spinka, op. cit., p.275.

[61] Jakoubek’s directives to the Hussite soldiers represent an accommodation of Christian ideals to national exigencies very much in the way in which, at a later time, The Souldier’s Pocket Bible of the Ironsides epitomizes the “just war” when over against “love your enemies” are set the verses “Do you help the wicked and love those who hate the Lord?” (Chronicles 19:2) “Do not I hate them, O Lord, who hate You?… I hate them with an unfeigned hatred as they were my utter enemies” (Psalm 139:21-22). Cf. Roland H. Bainton, “The Churches and War: Historic Attitudes Toward Christian Participation.” Social Action, vol.XI, 1 (January 15, 1945).

[62] Ibid., p.25.

[63] From the Hussite Anthem.

[64] The spirit of Nationality is a sour ferment of the new wine of Democracy in the old bottles of Tribalism. The ideal of our modern Western Democracy has been to apply in practical politics the Christian institution of the fraternity of all Mankind (“La démocratie est d’essence évangélique … elle a pour moteur l’amour.” Bergson: Les deux sources de la morale et de la religion, Paris: 1932); but the practical politics which this new democratic ideal in operation in the Western World were not ecumenical and humanitarian, but were tribal and militant.” Arnold J. Toynbee, A Study in History, London: Oxford University Press, 2nd ed., 1945, vol.I, p.9.

[65] Vivebat circa 1378-1424.

[66] Cf. Zahir-ad-Din Muhammad, Memoirs, translated by A. S. Beveridge, London, Luzac, 1922, vol.II, pp.35,409,550,564.

[67] The Battle of Mt. Vítkov in the summer of 1420 and the Battle of Mt. Vyšehrad in November 1420.

[68] The imperial and papal armies, composed of 40,000 cavalry and 90,000 infantry (over against 55,000 Hussites) had in its formations Spaniards, Frenchmen, Hungarians, Croatians, Germans, Sicilians, Wallachians, Jazyges, Ruthenians, Swiss tireurs, Dutchmen, Slovaks, Racians, Carniolians, and others. Count Francis Lutzow, Bohemia: An Historical Sketch, London: Chapman & Hall, 1896, pp.184-189. Concerning Cardinal Julian Cesarini, see Juan Palomar, page 69.

[69] Supra, pp.33,35.

[70] The Cambridge Medieval History, vol.VIII: “The Close of the Middle Ages,” Cambridge: University Press, 1936, p.87.

[71] The problem of the Waldensian influence on Chelčický is still a moot question. According to some writings, Peter Waldo, on account of the persecution of the Waldensians in southern France and Northern Italy, went to Bohemia with his coadjuteur Viveto in 1212. If tradition attributes his death to have occurred in 1218, that means that he must have spent six active years in Bohemia and Moravia. Furthermore, tradition names Klášter near Nová Bystřice, in the district of Jindřichův Hradec (Neuhaus) in southern Bohemia, as Waldo’s burial place. Chelčice, where Chelčický was probably born 170 years later, is barely 50 miles west of Klášter. Cf. Jean Jalla, Pierre Valdo, Geneva: Labor, 1934, pp.78-80. Johann Martinů, Die Waldesier und die hussitische Reformation in Böhmen, Vienna: Kirsch, 1910. See also Gindely’s and Goll’s books in the bibliography.

[72] The Cambridge Medieval History, vol.VIII, p.87.

[73] Probably sometime in 1455. Cf. J. Goll, Petr Chelcickv a Jednota bratrská v XV. století, (Peter Chelčický and the Unity of Brethren in the 15th Century), Prague: Historický klub, 1916, p.67.

[74] O původu Jednoty bratrské a řádu v ní, (About the Origin of the Unity of Brethren and the Order Thereof), Otakar Odložilík, ed, Prague: Reichel, 1928, p58f.

[75] N. V. Yastrebov, “Kogda napisal Petr Chelčický Repliku protiv Rokycany?” in Jub. Sbornik ke cti Dr. Karejeva, St. Petersburg, 1914; cf. CCH, 1914, p.80, LF, 1921, p.35f.

[76] Regnabat 1458-1471.

[77] From a report written in 1527 by Brother Lucas of Prague, quoted in Goll, op. cit., p.68.

[78] He was the nephew of Archbishop Rokycana of Prague.

[79] Palacký, op. cit., vol.IV, p.241.

[80] B. Vančura, Jednota bratrská, Prague: 1938, p.10; the founding of the church may have occurred in 1458; tradition says it was founded on the 1st of March. This is based on a writing by Lasicius who says, “Rex Vladislaus, corpore at aetate gravis, quippe natus Calendis Martiis 1456 (sic), quum se primum a Calixtinis avulsissent Fratres.” Cf. Go11, op. cit., p.68.

[81] The episcopal ordination was performed by Martin, a Waldensian elder from Vienna. It is interesting to note that during this early period the Brethren administered the communion “in the apostolic fashion,” i.e. without priestly vestments, while the participants took, sitting, plain bread, and wine served in earthen cups. Cf. Müller-Bartos, Dějiny Jednoty bratrské, (History of the Unity of Brethren), Prague: l923, p.35.

[82] Goethe, Torquato Tasso, iii, 2.

[83] Spinka, op. cit., p.291.